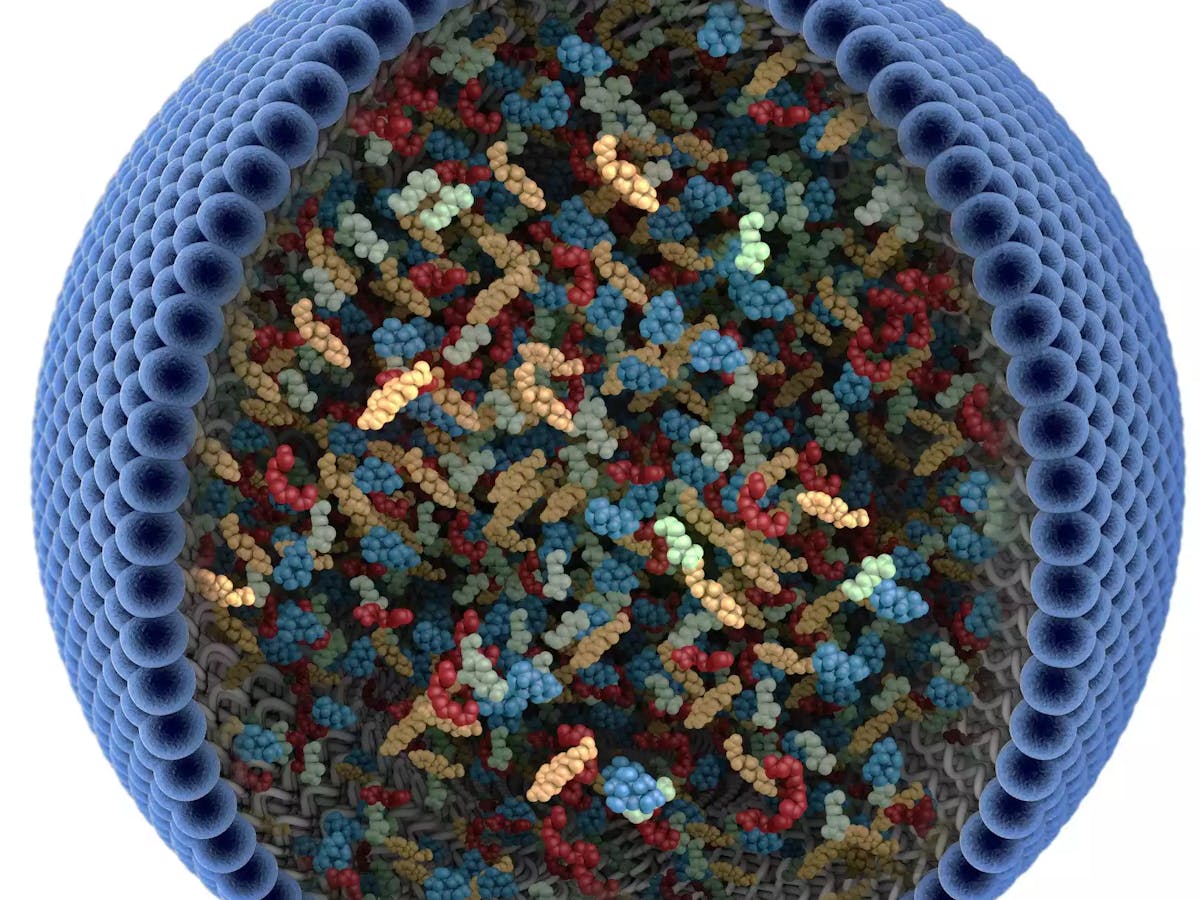

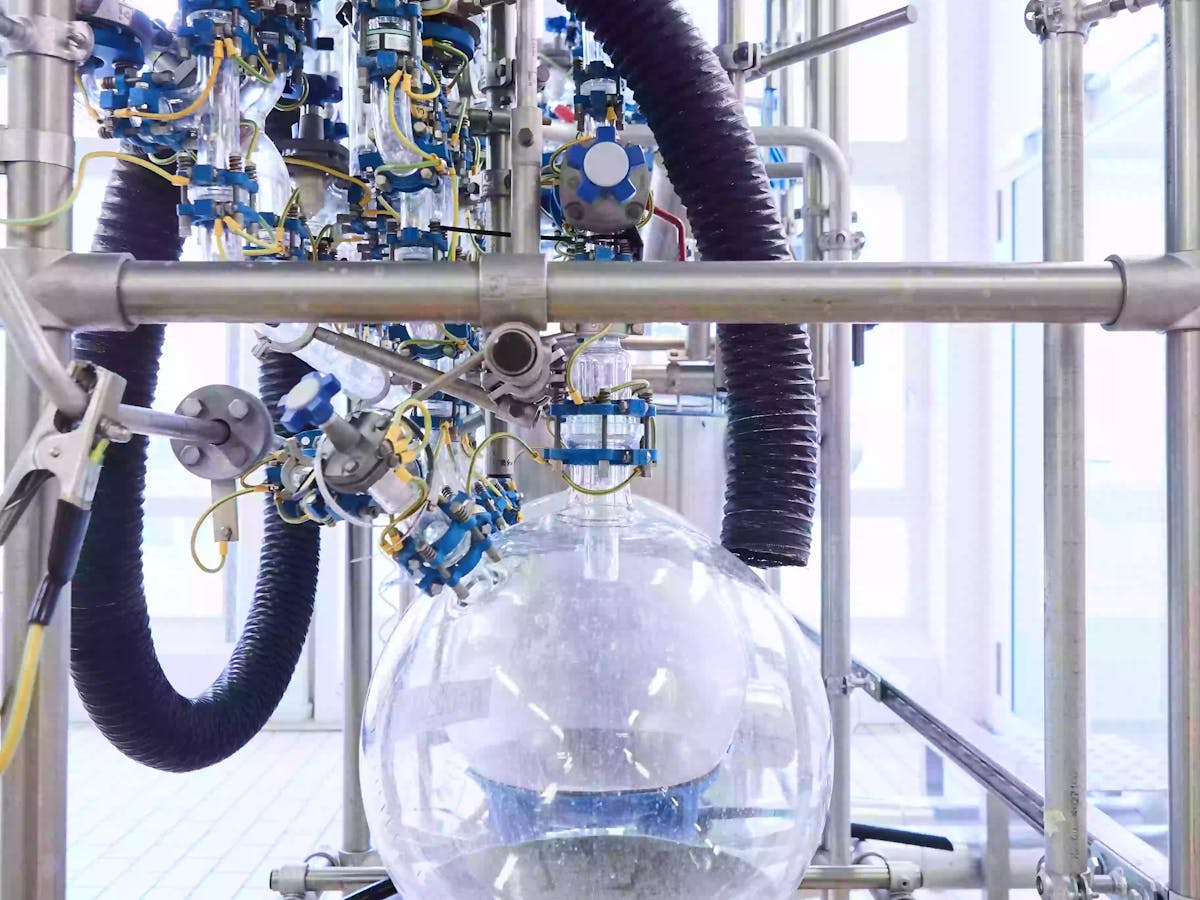

Bruce Lipshutz was among the first scientists to look into designer surfactants as a replacement for toxic solvents. These soap-like particles, which form into spherical shapes, can trigger chemical reactions in water. Fabrice Gallou from Novartis joined him early on in these efforts.

Table of contents

Table of contents An old science

An old science Water chemistry

Water chemistry Green gains

Green gains New norm

New normPublished on 03/09/2020

Fuming smokestacks and the pungent smell of burning coal were once signs of civilizational progress and industrial advance, powered by breakthrough discoveries in chemistry which were at the forefront of scientific progress during the 19th and early 20th century.

But these times are long gone. Chemistry has lost its prior luster as many of its once lauded discoveries such as plastic, fertilizer and radiation, which have changed our lives so completely and helped us industrialize societies in the first place, are now considered toxic and an outright threat to human life on earth.

Since Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book Silent Spring, which was published in 1962 and in which the author highlights the consequences of industrial pollution, civilization and chemistry, once used almost synonymously, seem at odds with each other.

Though efforts to make chemistry greener and to use different methods for producing new environment-friendly materials have been stepped up in the late 20th century, their use so far is limited given that it is hard to replace classic fossil-based chemical processes.