Eyes and intellect

Theodor Grauer is a witness to a bygone era. He dedicated his entire professional life to research, starting at Geigy in 1946 and ending with his retirement in 1983. The chemist worked continuously on the front line in the laboratory, conducting make-or-break experiments.

Text by Peter Herzog

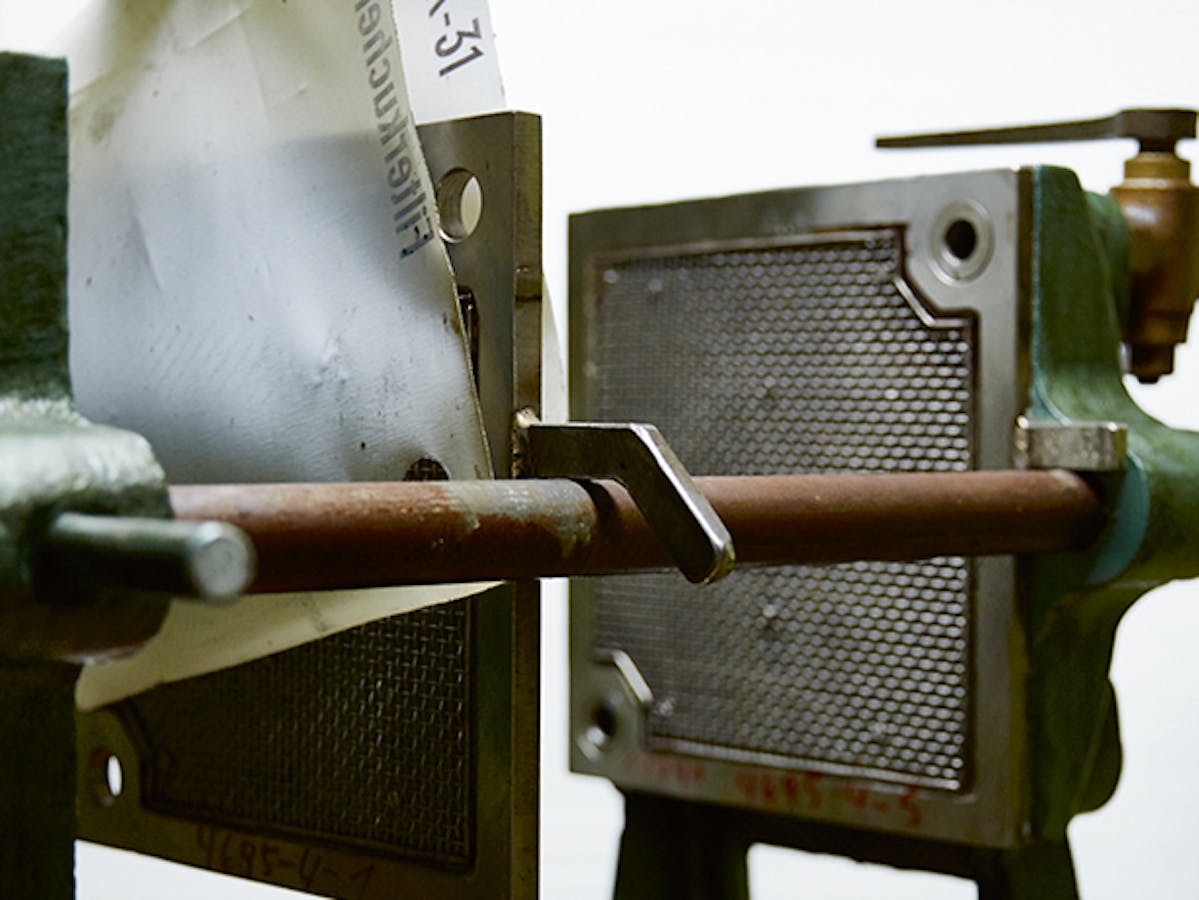

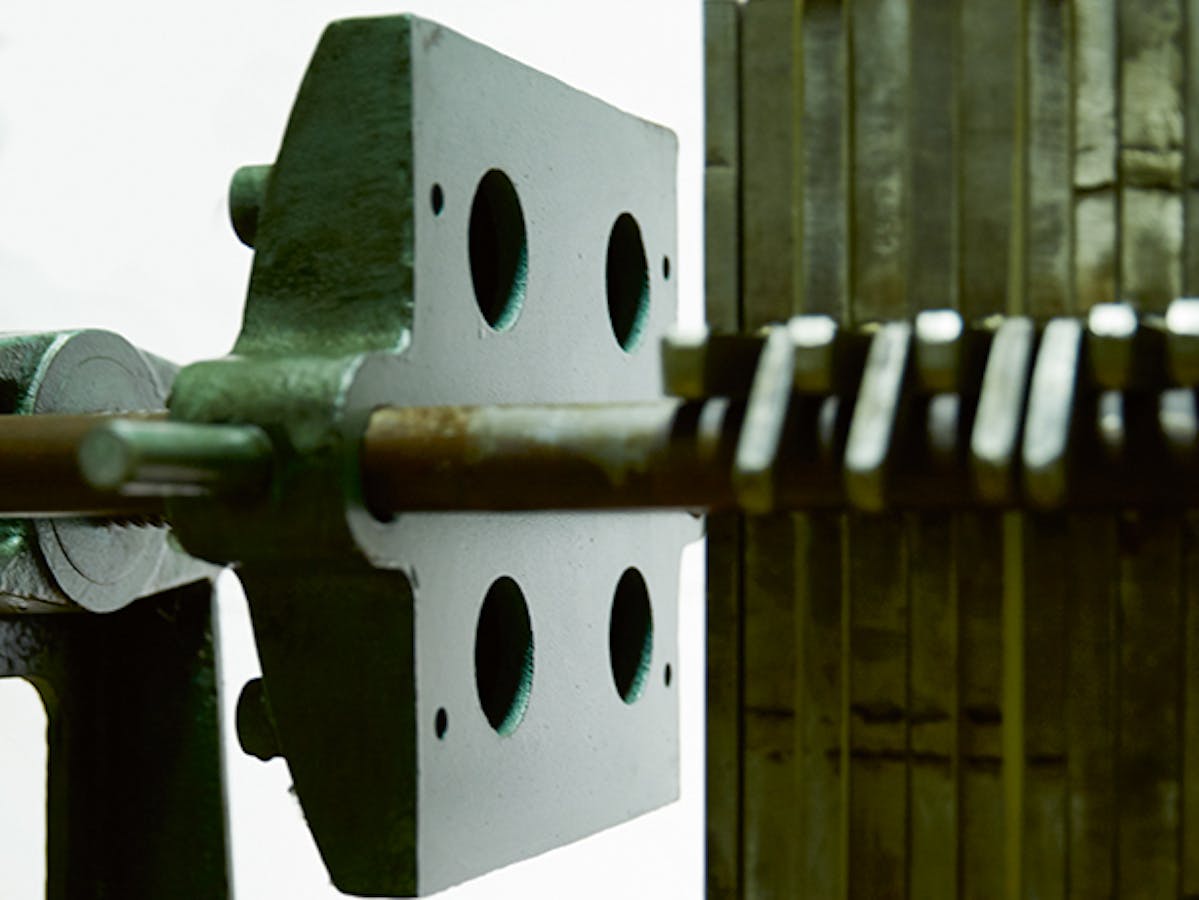

Filter presses were used for the solid-liquid separation of substances.

Table of contents

Table of contents Chemist and semi-professional musician

Chemist and semi-professional musician Eyes and intellect

Eyes and intellect Environmental protection

Environmental protectionThis article was originally published in October 2015.

Published on 24/06/2020

When Theodor Grauer read the article in the 6–7/2014 issue of live about Cesare Sgueglia’s Unicum Museum comprising objects spanning over 150 years of Basel’s chemical and pharmaceutical history, his memories were rekindled of his time as a chemist at Geigy and Ciba-Geigy in Schweizerhalle and his prolific professional life: Immediately after completing his studies at the Polytechnic Institute in Zurich in 1946, Theodor Grauer started his career at Geigy. He always worked in the laboratory in Schweizerhalle where make-or-break experiments were conducted, right through to his retirement in 1983. But Grauer was also involved in the launch of new products. He visited many countries and can remember business trips to Mexico, Italy and the USA.

Reading about the museum in live reminded Theodor Grauer of the filter press that had been sitting in his garage for 30 years. He was given the model, which measures around a tenth of the size of an original filter press, when he retired from Ciba-Geigy. It is literally substantial gift as the model weighs around 300 kilograms!

live visited the retired chemist at his home in Arlesheim. On November 3 he celebrated his 96th birthday. He has been married to his wife Regula for 64 years. His legs cannot carry him as well as they used to and he has to rely on a walker, which prevents him from nurturing and maintaining his magnificent 2400-square-meter garden – something he has been passionate about for over 50 years.

“We are in the process of clearing. We wish to sell the house and move into a retirement apartment as soon as one becomes available,” he explains on our arrival. And he adds that the time has also come to part with the utensils from his professional life. He had therefore called Cesare Sgueglia and offered him the filter press for his museum; the curator was delighted to accept the offer.

Meanwhile Theodor Grauer and his wife have moved into the Tertianum retirement home at St. Jakob Park.

Filter presses played an important role in the everyday professional life of Theodor Grauer. They were used for the solid-liquid separation of suspensions: “You would let a mixture of substances (suspension) flow into the cloth-lined chambers where they were placed under high pressure. The liquid passed through the filter medium and exited the press via outlet channels. The filter cake fell into the wooden boxes placed under the press and was dried. This, in simple terms, is how dyes were created,” explains Theodor Grauer. Today, he adds, this procedure is of course obsolete.

The look behind his spectacle lenses scrutinizes the visitor attentively and his eyes sparkle. The memories of his professional life are present and his powers of recollection are astonishing. These are stories from a bygone time. “Although I’m a scientist, I was a semi-professional musician in my free time,” he laughs. “I played the viola and violin in four different orchestras and had my own string quartet; I therefore know almost all the works of Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert and Mozart and still have them all in my head today at the age of 96.” He starts warbling in the middle of talking: “Da, da rampampom – that’s the melody of the string concerto opus 18, number 1.”

Music, riding, collecting stamps and cultivating his large garden were his hobbies. In the army he was in the cavalry and held the rank of captain, as he underlines not without pride. Horses therefore also became an important part of his life.

He spent hours in the garden working on his hands and knees. Sometimes this was laborious but he did it with great pleasure and enthusiasm. He needed all this in order to provide a balance to his work-ing life and be able to switch off. “The responsibility that I had as a chemist on the front line was enormous,” he says.

“We had little equipment. We used our eyes and intellect in the laboratory to observe the chemical processes.” He always worked with critical products, he emphasizes. It was under his leadership that crop protection agents, optical brighteners, pharmaceutical precursor products and dye precursors were manufactured. He spent over three years working on the mothproofing agent Mitin®, “because for a long time we were unable to find any solution for filtering it.”

In those days the noise from the machines in the workshop was still considerable, with rattling and clattering. He had therefore become a rather loud person in the course of his life, he confesses, and raises his voice an octave: “Close that!” he shouts in a quivering voice through his living room to illustrate how he had to communicate with his colleagues during experiments.

He adds that there were also some accidents. He can remember the worst one to this day. Back then, around the mid-1950s, 300 kilos of aluminum chloride and four tons of nitrobenzene caught fire. “The boiler exploded, the building was engulfed and we had 23 injured colleagues. I will never be able to forget that accident, and the emotions are still there today after almost 60 years.”

Fortunately, the risk of such accidents is much lower today. Thanks to inprocess computer analysis, the safety of everyone has been improved several times over. Back then, accidents were the reason why efforts were intensified in the chemical and pharmaceutical sector to enhance safety and the protection of the environment. “After the merger to form Ciba-Geigy in 1970, the first waste treatment plants were installed at Schweizerhalle,” recalls Theodor Grauer. He himself initiated the first soil-water-air unit for associates and residents in Muttenz, an odor reporting center, as he explains. He received the emergency telephone calls in his office at Schweizerhalle and in the night they were diverted to his home in Arlesheim. There were times when the phone in his bedroom rang at 3:00 a.m. and a voice at the other end of the line said: “Mr. Grauer, please come immediately! There’s a terrible stench here.”

It was also at this time that Theodor Grauer wrote his 10 principles of clean production that are still applied today in the chemical and pharmaceutical sector. These principles will in future be on display at the Unicum Museum, the retiree adds. A laboratory flask with a stand in which chemical reactions were observed and which Theodor Grauer saved from the trash can is being donated to the museum too. However, the elderly chemist will not be visiting the museum himself. “At my age I hardly leave the house,” he explains. But he is pleased to have found someone in Cesare Sgueglia who can take over his legacy and who as an environmental specialist is not only capable of showing due appreciation of Theodor Grauer’s achievements but also of making his work accessible to the public at large and upholding its spirit.