Tree by tree, a new landscape...

Table of contents

Table of contents Classic with exotic accents

Classic with exotic accents Search for a symbiosis

Search for a symbiosisPublished on 30/05/2022

Just a few decades ago, trees were a rarity on the St. Johann industrial site in Basel. More tolerated than consciously planted, they grew in niches next to railway tracks and closely spaced laboratory buildings, production halls and office blocks. At the time, large-scale parks were unheard of.

This changed with the Campus master plan, which was designed in 2001 by the Italian urban planner and architect Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, who included natural spaces in his building concept. Since then, several green areas have been created, which are not only a feast for the eyes, but also help employees relax and unwind or give them the opportunity to hold informal meetings – be it in a secluded wood or sunbathing on the spacious meadows.

One of the largest parks is the so-called Park South, which has formed the southern border of the Campus since 2007. With over 1000 trees, the park represents a green oasis with a colorful fauna and flora that invites you to stroll and relax.

Pristine landscape

The importance of the park goes far beyond the mere accumulation of trees and shrubs. Here, an attempt was made to recreate an early landscape that is now hidden under dense settlement structures: the original landscape of the Basel Rhine Valley, which was formed by glaciers and rivers.

The project was developed by Vogt landscape architects from Zurich in cooperation with the general planner team under the direction of Stauffer Roesch landscape architects from Basel. Both offices have a great deal of experience in planning and implementing urban open spaces.

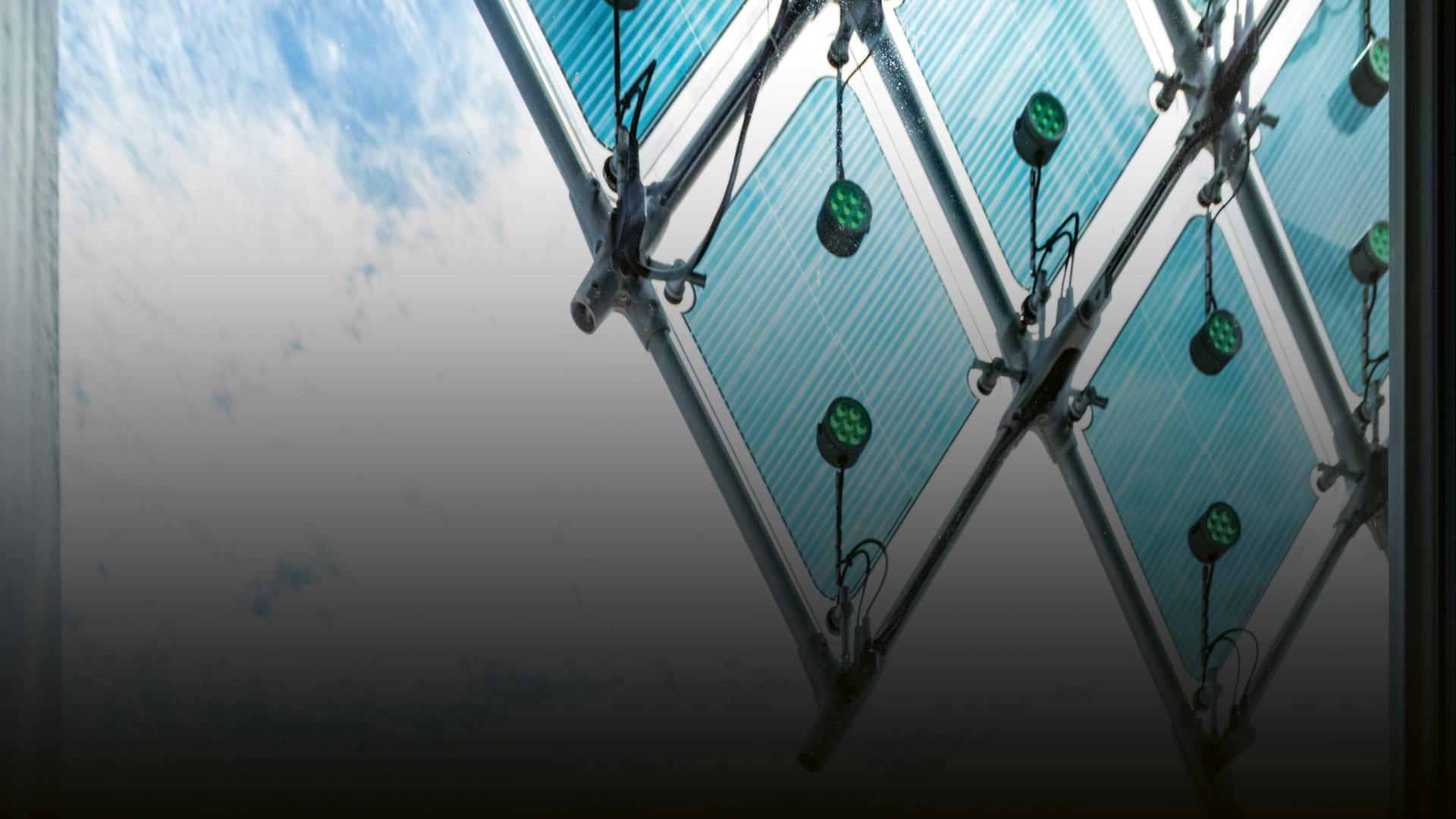

In addition to Park South, Stauffer Roesch implemented many of the larger green spaces on the Novartis Campus, including two large parks and the Physic Garden, which boasts a collection of medicinal plants to remind visitors of the origins of medicine. Vogt, on the other hand, were responsible for the design of the green space in front of the Gehry Building on the Novartis Campus as well as Rahul Mehrotra’s laboratory building, which stands out for its innovative green façade and lush interior spaces.