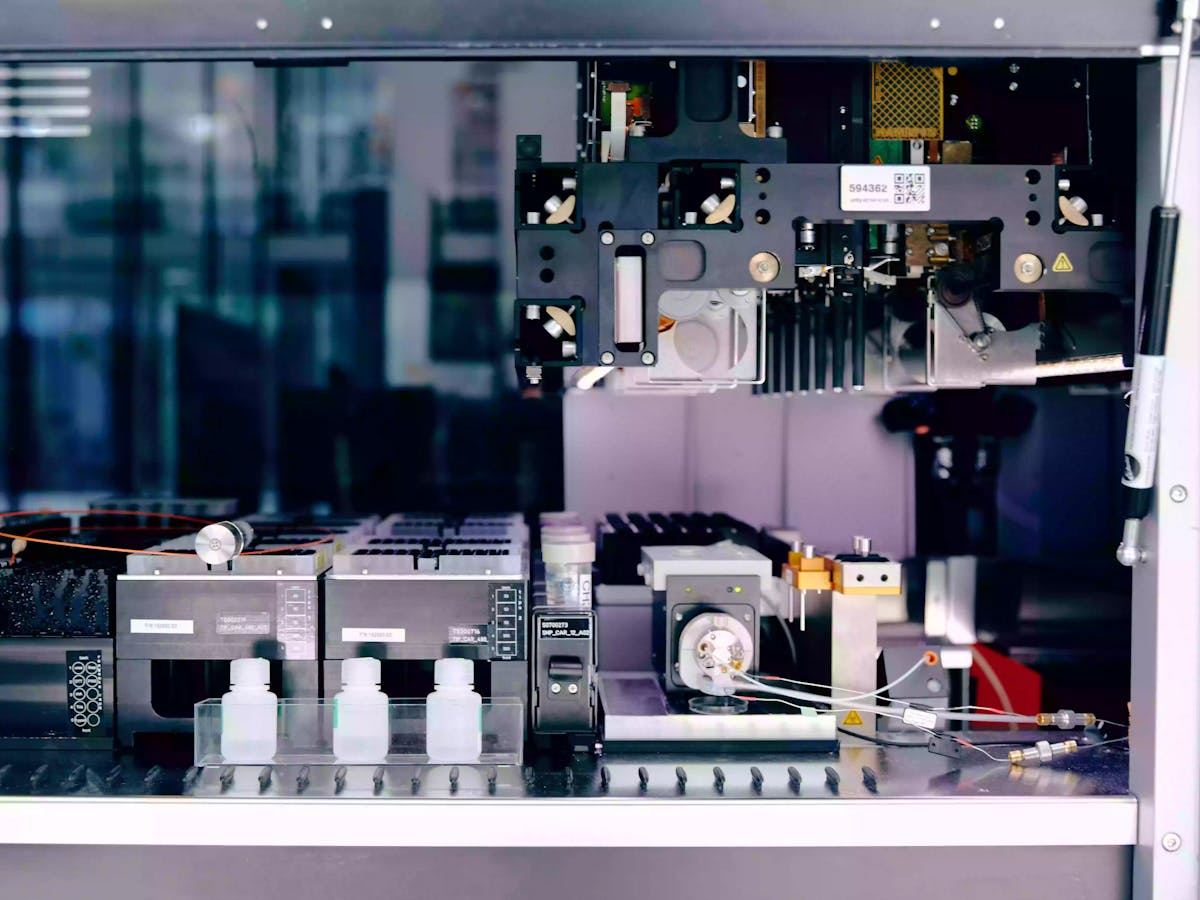

Close-up of a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

Table of contents

Table of contents Previously undetectable

Previously undetectable Conscientious throughout the pipeline

Conscientious throughout the pipeline Readily biodegradable by design

Readily biodegradable by designIn an ideal world, pharmaceuticals would never reach the environment. Patients would use them for their benefit and the pharmaceutical activity would vanish like a patient’s disease. But this would be too simple. Through normal use, misuse, inappropriate disposal, and limitations in wastewater treatment facilities, drugs can enter the environment.

The first time this phenomenon rose to prominence was in the 1990s, when veterinarians in India used a widespread painkiller to treat cattle. Because cattle aren’t eaten in India, dead cattle were typically left for the vultures. Although harmless for human beings and animals, traces of the chemical compound were lethal for the birds, leading to the decimation of vulture populations around the country.

“People just weren’t thinking about micropollutants much before that,” says Jutta Hellstern, Head Water Resources, who has been leading several of the efforts at Novartis to address pharmaceuticals in the environment. “But since then, there’s been increasing interest in the impacts on non-target organisms like fish and algae – and people are starting to worry about their drinking water too.”

Over the past decades, regulatory agencies and academic researchers have also found traces of contraceptives, antidepressants, and antibiotics in public wastewater and aquatic environments. But the extent of the problem is not yet fully understood and regulations are sparse. Initiatives such as the E.U. Water Framework Directive are working to gather more information about the scale and impact of pharmaceuticals in the environment, as well as beginning to explore potential solutions.

To help minimize active pharmaceutical ingredients, often abbreviated as APIs, in the environment, Novartis has established more environmentally conscious protocols for every step of its value chain.

On top of that. Novartis has also joined an ambitious Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) public-private project – called Prioritisation and Risk Evaluation of Medicines in the EnviRonment (PREMIER) –, which aims to better understand this field and to seek tools to make new APIs environmentally friendly by design.