Published on 05/04/2021

The late autumn sun in the year 1984 was already low when we refueled a 76 Ford station wagon in Death Valley Junction, about 150 kilometers northwest of Las Vegas. The 5.8l V8 engine of the almost six-meter-long vehicle, which we had bought for 500 US dollars, consumed about 20 liters per 100 kilometers. A gallon of unleaded cost about 80 cents, a full tank less than 20 dollars. Life was carefree, the radio stations were playing Tina Turner, Van Halen and Madonna over and over. We didn’t waste a single thought on our car releasing more than 160 kilograms of CO2 on the road from Las Vegas to Death Valley, nor that we would emit about 1.8 tons of CO2 on the whole trip through the USA. We drove past Zabriskie Point into the valley. At a party in Furnace Creek, the band played Take It Easy by The Eagles.

26 000 cars on the road

If the Novartis car fleet were to consist of nothing but Ford station wagons, its CO2 emissions would amount to around 611 000 tons of CO2. This would be more than two-thirds of the total current greenhouse gas emissions of Novartis (nearly 900 000 tons).

In reality, the car fleet of 26 000 vehicles is composed of 18 different categories. The range extends from so-called utility cars such as a Ford Ka or Citroën C1 to limousines like the Audi A6 or BMW 5 Series and luxury SUVs such as the Volvo X90 or VW Touareg.

They mainly use diesel and gasoline motors on the various roads and highways, with only 10 percent of the fleet powered by hybrids, plug-in hybrids, electric and pure ethanol engines.

On average, each Novartis car covers 30 000 kilometers per year. That corresponds to an annual median of 5.2 tons of carbon dioxide per vehicle. My station wagon had emitted more than 22 tons of CO2 per year into the atmosphere. Unacceptable from today’s perspective.

Huge savings potential

“Achieving the fleet’s target for reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in relation to the Novartis 2025 climate goals is sometimes a difficult and complex matter,” says Laszlo Kiss, Global Senior Procurement Category Manager, Global Fleet.

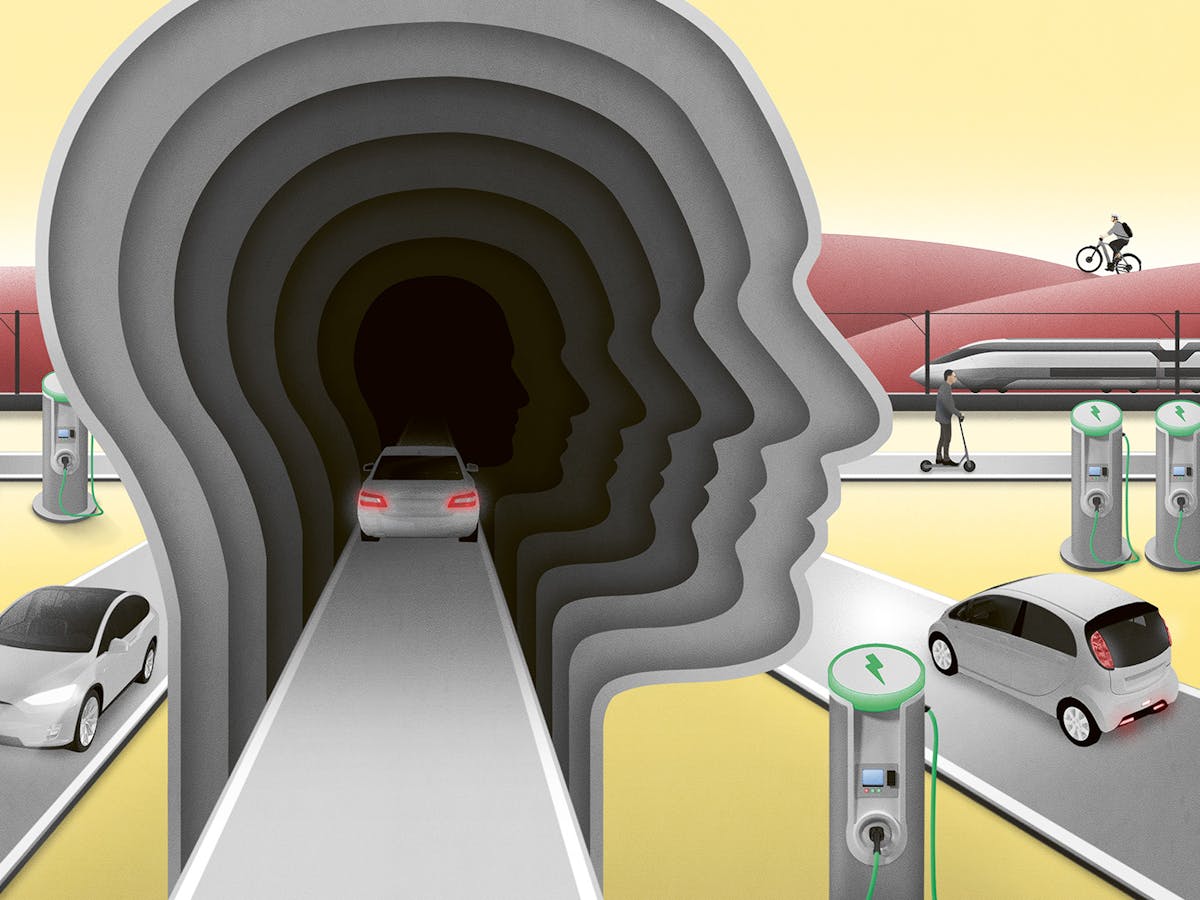

This goal also completely redefines the job of a fleet manager. Whereas in the past, the best quality for the lowest price was the norm when purchasing new cars, carbon neutrality is a completely new factor, and the decision as to which vehicles to include in the fleet needs to be based on new criteria.

One can imagine that this is not so easy, because the 26 000 vehicles, with most of them field-force cars, operate on the roads of some 79 countries. They are found on Route 66, as well as on the Champs-Elysées, the Pan-American Highway and the Silk Road.

An experienced driver brings urgently needed medicines to their destination via a trans-African highway; a sales manager drives through the urban canyons of Shanghai; and a biodiversity specialist visits a reforestation farm on the edge of the Colombian jungle.

“If all of these vehicles were electric, or at least equipped as plug-in hybrids or hybrid vehicles, this would naturally amount to huge savings in greenhouse gases and thus be a big step towards the CO2 targets set for 2025. At present, 90 percent of the fleet consists of vehicles with combustion engines. Replacing them step by step with plug-in hybrids and e-cars is a difficult task,” admits Kiss, who has been working as global fleet manager at Novartis for a year.

No charging station at every road

The worldwide network of paved and unpaved roads currently measures about 32 million kilometers. Of these, about 6 million are located in Central Europe. For every 6 million kilometers there are about 120 000 charging stations, i.e., on average every 50 kilometers electric cars can be recharged. This is probably the world’s densest network of charging stations for electric and plug-in hybrid cars.

While, on average, coverage looks great, the devil is in the detail: Actually, only Norway and the Netherlands have an almost nationwide network that provides electricity in sufficient strength and at reasonable charging speeds.

In many other European countries, the situation is far from ideal. For example, a trip on the Autostrada del Sole to the south of Italy must be well planned. Many charging stations are still located outside the highway, only a few at the rest stops and filling stations. The charging time of larger batteries is still about 40 minutes. And whether the charging stations are free of charge is another uncertainty.

“What makes things even more difficult for our fleet is that in the remaining 54 countries outside Europe where our vehicles are used, the infrastructure for the widespread use of plug-in hybrids or e-cars is too sparse or simply not available at all,” explains Kiss.

Kiss and his team are constantly analyzing the political, economic and social situation in all countries where Novartis is present and where there are fleet vehicles on the roads. The analysis shows which milestones the respective countries or regions have reached on the road to the age of electric cars. The results provide the team with a basis for decisions on the timing of country-specific adjustments to local fleets.

“The range of and access to charging points is one of the most important indices for assessing when and where we increase usage of e-cars. In this manner, we are progressing meter by meter on our road to carbon neutrality,” says Kiss.