Table of contents

Table of contents The mother of medicine

The mother of medicine The development of chemistry

The development of chemistry A golden era of research

A golden era of research A new attempt

A new attemptThis article was originally published in April 2014.

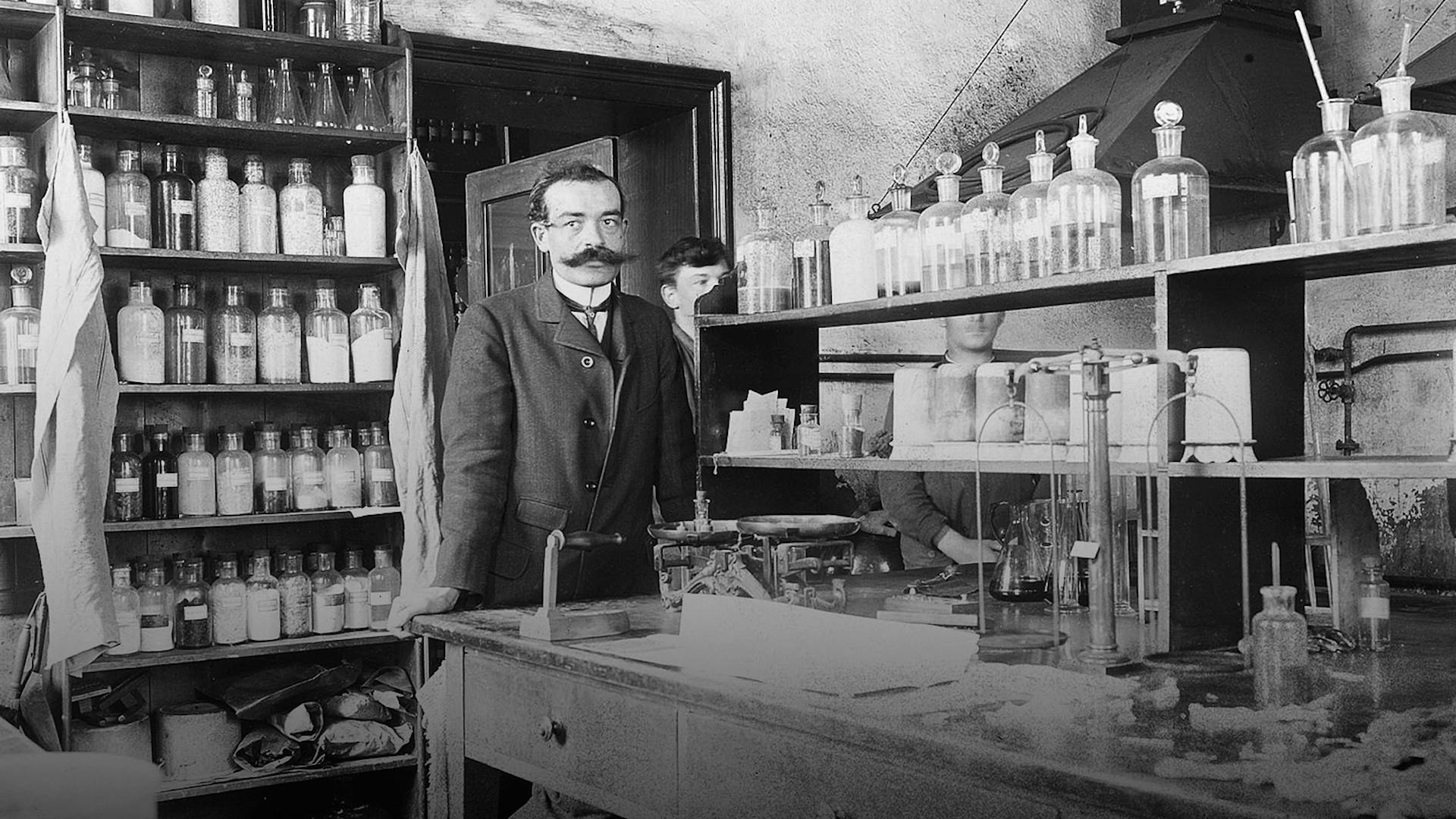

It must have been a hectic day in the laboratory of London’s St. Mary’s Hospital when Alexander Fleming got ready to leave for his summer vacation. It is no longer possible to say exactly what went on, too much has happened since then, but there were letters to write and send, and the last experiments that the Scottish bacteriologist had conducted likewise had to be documented and properly written up. It occurred to him that someone ought to have carried out a thorough cleaning of the lab, but that never happened. Fleming closed the door behind him, said goodbye to his colleagues, went to the station and sat down on the train that took him to the southern coast of England, where he planned on relaxing for the next few weeks. A Petri dish with a bacteria culture, an item he had forgotten all about in the last few hectic hours, remained where it was, unnoticed.

This, or something like it, is how one of the greatest discoveries of medical research could have started. Fleming later recalled the exact details about September 28, 1928, the day he returned from his vacation and with some astonishment viewed the mess he had left behind in the laboratory. As he stated years later when he had already been awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery of penicillin, he would hardly have thought that this day would mark a fundamental change in the history of medicine. “However,” remarked the Scottish researcher laconically, “that’s exactly what happened.”

Instead of simply throwing away the forgotten and apparently dirty Petri dish with the staphylococci, he examined it in more detail. He noticed that a mold had developed in the middle, and all around it the dangerous staphylococci had died. His assistant pointed out that this could perhaps be exactly the thing they had been searching for all this time: a powerful substance that would kill bacteria.

Fleming, who served in the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War I, had dedicated himself to bacteriology and was persistent in his search for an effective antiseptic. During the war, he had witnessed in person how doctors could only stand by and watch as hundreds of thousands of soldiers died from bacterial infections. Even a slight wound incurred through a cut with a razor blade could easily prove fatal.

Fleming first looked for what are known as autovaccines and in doing so addressed the question of how body orifices such as the eye are able to fight off the onslaught of bacteria and other foreign bodies. He then discovered the lysozyme enzyme, which appears in many human bodily secretions such as tears and can kill bacteria. The discovery of penicillin from the mold of the Penicillium genus, which was much more effective than lysozyme, proved a real scientific breakthrough and was to revolutionize medicine.