Live. Magazine

In the early years of the new millennium, the medical community was euphoric. The first personalized cancer drugs had arrived on the market and new ones were in the pipeline, raising hopes that this age-old disease could finally be overcome.

Novartis was among the early movers and had a strong pipeline of new therapies ready for launch. But even as the world celebrated the breakthroughs in cancer research, some scientists found that a persistent number of patients did not respond to the treatments due to drug resistance that were triggered by new mutations.

This also raised the interest of Novartis researchers Wolfgang Jahnke and Andreas Marzinzik, who hit upon a molecule that could address this resistance challenge. But their idea was badly timed and fell on deaf ears as the entire industry was enthused by the success of the newly launched cancer medicines. Overall, most industry experts regarded the drug resistance issue as a minor challenge that would be resolved soon by the next generation of treatments. “At the time, no one was really interested in our approach,” Wolfgang Jahnke said. “The general groove was that the books were closed for this chapter in medicine.”

Going underground

Jahnke and Marzinzik struggled to take no for an answer and went underground with their idea by starting a grassroots project. They were convinced that the drug resistance issue could soon boomerang and dampen the reigning upbeat mood.

They drummed up support and worked on their molecule as a sort of side car next to their daily duties. “Although there was no official interest,” Andreas Marzinzik remembered, “we were able to run the project as a small venture because we won support from some of our colleagues who helped us test our idea.”

Today, such grassroots projects are less rare and even supported by Novartis. Several years ago, Novartis started the Genesis Labs Initiative, which allows scientists and engineers to pursue ideas that are out of the company’s core discovery scope and encourages bold research, while keeping the focus on major scientific efforts undiminished.

“It was a classic example of the type of multidisciplinary endeavors that are supported now through the Genesis Labs,” Marzinzik said. “Our project followed a clear bottom-up approach because we believed in what we were trying to achieve – we were starting small, but with a very strong hypothesis.”

While real-world data showed persistent drug resistance in some patients, the idea for their approach came from the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation, or GNF (now Novartis Biomedical Research San Diego), which identified a molecule in a screen, which Jahnke and Marzinzik thought could work.

Far-out ideas

“It all started with that GNF molecule,” said Jahnke. “Their initial experiments showed that it operated unlike anything else the company had in the pipeline – but nobody knew exactly how it worked.”

The most likely explanation was that the GNF molecule was not acting through the active site on the disease-triggering protein but rather through another, less explored location, which no drug had ever been designed to target before.

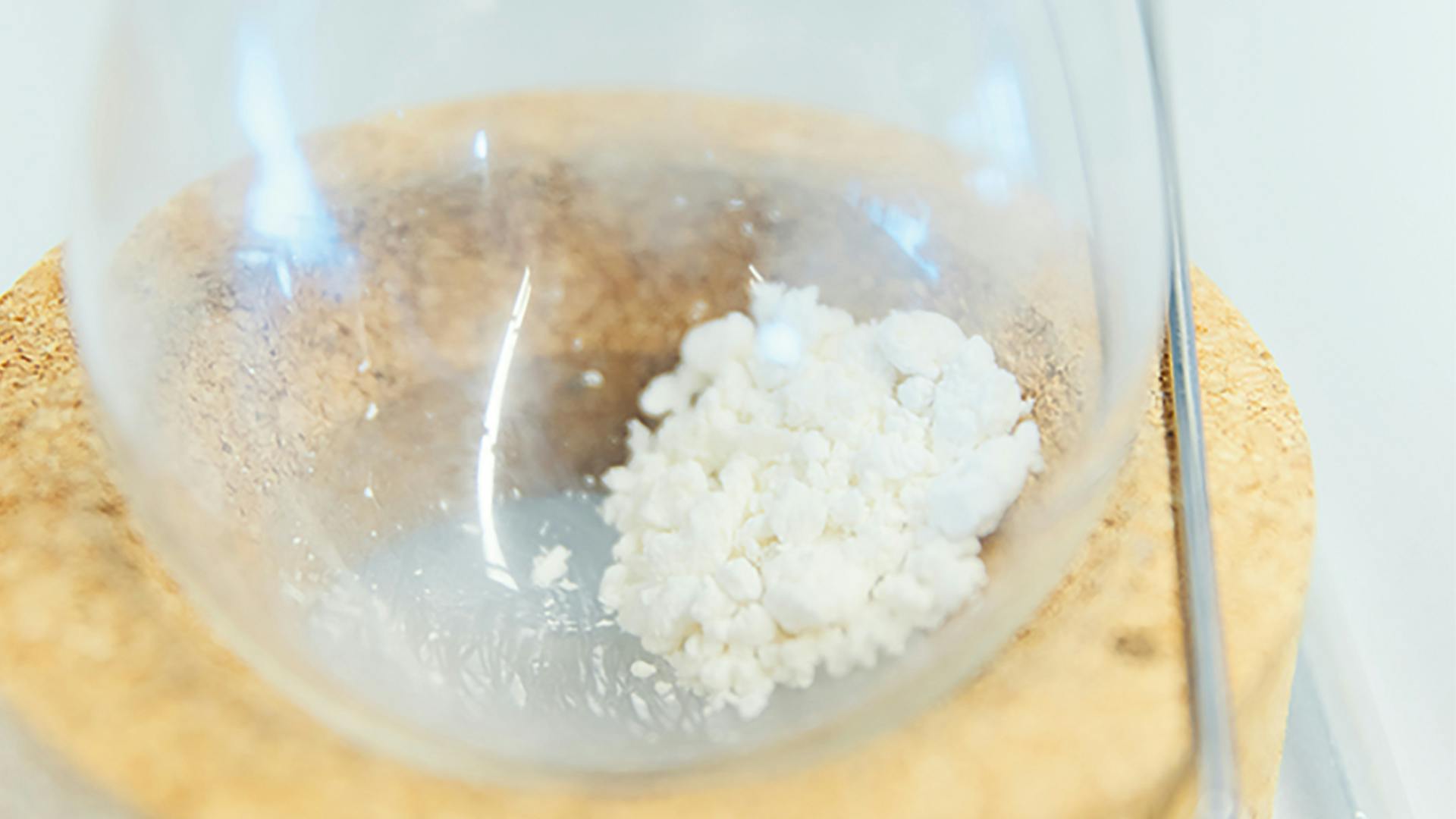

Classic chemical work is a mainstay at the lab of Andreas Marzinzik and Wolfgang Jahnke.

Compounds are tested continuously.

Traditional chemistry tools are ubiquitous.

Compared to the active site of a protein, the functions of so-called allosteric sites are often not well understood. Worse, allosteric sites are often “cryptic,” meaning that they are only visible at some stages of protein activity – and the role of these allosteric sites in protein activity is often unclear.

All of this only heightened the curiosity of the two researchers and their colleagues, who wanted to learn more about the GNF molecule’s mechanism and potential function.

“In collaboration with our colleagues at GNF, Novartis Biomedical Research and the Biozentrum Basel, we employed top-notch structural and biophysical technologies to elucidate its mechanism,” said Jahnke. “And that’s how we discovered that it bound to this allosteric site that could be a brand-new drug target.”

Classic chemical lab work still forms the basis of pharmaceutical research.

But one of the key aspects in this work is not just the technology. It's working with diverse partners with a wide set of skills and experience.

Starting small

The GNF molecule didn’t have the right characteristics for development into a drug, but it revealed where the disease-triggering protein had a weak point outside of the active site.

Although there was no financial support to pursue their finding as a drug discovery project, through a stroke of serendipity, they happened to have funding to use and further develop an exploratory technology that was the perfect match to look for allosteric molecules.

“One of the challenges of allosteric binders is that they are often silent – that means they don’t show up in assays of protein function and so you need to design different tests that are sensitive enough to detect them,” said Jahnke. “By lucky coincidence, the technology we were using was exactly what we needed.”

This technology – called fragment-based drug discovery – contrasts with typical drug finding screens because it begins with smaller chemical building blocks – just fragments of a normal drug.

The screens look for the bits and pieces that show any binding activity to the protein. If any are found, those fragments can be optimized and assembled into a full-size drug molecule.

The strengths of this piecemeal method are that novel chemical matter can be found by building up the molecule from smaller pieces, and that no functionality is needed to detect them. Indeed – and this is somewhat of a drawback – the fragments themselves often have no effect in typical protein function tests. Hence, the strategy requires much more sensitive instruments, such as nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, or NMR.

These instruments have been helping life science researchers visualize proteins and smaller molecules for decades and Jahnke has spent most of his career specializing in their use.

NMR uses strong magnetic fields to reveal the shapes of molecules, tapping into the same principles as medical magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, which produces images of the inside of the human body. But using NMR to detect fragment binding was a very new application, and there was no guarantee it would work.

“We didn’t know what to expect, but those experiments were an amazing success,” said Jahnke. “The technology was so powerful that we could identify and optimize many fragments, and we learned a lot about both the fragment-based method and also the protein and its allosteric site.”

To understand a chemical compound, ...

... researchers need to analyze its structure.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, or NMR, is a powerful biophysical imaging technique.

Persistence paid off

Despite the initial success, support remained limited, and the team reached a point where they simply couldn’t do much more without funding. So, they published some of their results as an academic exploration and let the project drop for over a year.

Then, things started to change. “Back in the 2000s, the field of oncology probably underestimated how big the resistance problem would turn out to be,” said Jahnke. “But it was already obvious in the early 2010s that the first and second generation of cancer drugs weren’t always a lasting solution and there was still a clear unmet medical need.”

This shift in perspective gave Jahnke and Marzinzik a chance to pick up the work where they had left off. They proposed their research again, and this time it got the go-ahead as an official drug discovery project. This brought the project into its second stage, with involvement of chemist Joseph Schoepfer and molecular modeler Pascal Furet and many more dedicated scientists as part of the interdisciplinary team, which led to the development of a new drug.

“From then on, we had the funding and multidisciplinary collaborators we needed to turn our initial findings into a drug candidate – which was still no easy journey,” said Marzinzik. “The fragment-based approach gave us a starting molecule, but there was a lot of work and ingenuity needed as our teams optimized the molecule into a drug candidate.

A few years down the road, Jahnke’s and Marzinzik’s persistence paid off big time. The result: a first-in-class drug that is helping patients with drug resistance who were left behind by the previous generations of oncology drugs.

Andreas Marzinzik: Starting with a strong hypothesis.

Wolfgang Jahnke: Starting small to get a big impact.

Overcoming drug resistance

But their allosteric compound has the potential to do much more. From the start, Jahnke’s and Marzinzik’s ultimate idea was to use allosteric and active site-targeted drugs simultaneously to prevent the emergence of resistance permanently in this particular cancer.

The hypothesis is that even if the disease-triggering protein mutates in the active site, it would still be blocked by the allosteric drug, and vice versa. Proteins can only tolerate so many mutations at a time before they lose all function. So, the reasoning is that it is extremely unlikely that resistance can develop in both places at the same time.

Supporting this hypothesis, preclinical experiments using the drug combination have shown no signs of resistance so far and these treatments will soon be moving into clinical trials.

“We started small, helping a few patients, but this strategy could be applied to all kinds of oncology targets,” said Marzinzik. “Everyone sees the opportunity now, and how well it can work, so this could be the next paradigm change in the treatment of cancer – one that finally prevents cancer from coming back.